Rating:AAAAA

Key Words:World Cultural Heritage,Museum,

The Forbidden City was the seat of Imperial power for 500 years, and it is now one of China s major tourist attractions

Location:

Located in the heart of Beijing, the Palace Museum is approached from the south through the Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tian'an men). Ten-meter-high walls and a fifty-two-meter -wide moat surround the palace. Measuring 961 meters from north to south and 753 meters from east to west, the expansive architectural complex covers an area of 1,110,000 square meters. Each of the four sides has one gate, namely, the Meridian Gate (Wu men) on the south, the Gate of Divine Prowess (Shenwu men) on the north, the Eastern and Western Prosperity Gates (Donghua menandXihua men).Immediately to the north of the Palace Museum is Prospect Hill (Jing shan, also called Coal Hill), while the Wangfujing and Zhongnanhai neighborhoods lie to the east and west, respectively. Visitors will be excited to find a wide variety of historic sites, scenic parks, shopping malls, museums, and theatres in the vicinity of the Forbidden City. Conveniently located bus stops and subway stations provide easy access to transportation.

Admission: 60 RMB (April - Oct.); 40 RMB (Nov. - March)

Opening Hours: Peak Season: 8:30-17:00 (Apr. 1st to Oct. 31st)

Off-season: 8:30-16:30 (Nov. 1st to Mar. 31st)

Phone: +86 10 65132255

Best Time to Visit: April to October

Recommended Time for a Visit: 3 Hours

The Palace Museum was commissioned by the third Emperor of the Ming Dynasty, Emperor Yong Le. The palace was built between 1406 and 1420, but was burnt down, rebuilt, sacked and renovated countless times, so most of the architecture you can see today dates from the 1700’s and onward. The Forbidden City was the seat of Imperial power for 500 years, and is now a major tourist attraction in China.

The total area of the complex is 183 acres, so it takes quite a while to walk through, especially if you want to have a close look at everything. All together there are 9,999 1/2 rooms in the Museum, not all of which can be visited. The Imperial Palace is rectangle in architecture. It is 961 meters long from south to north and 753 meters wide. There is city wall which is 10 meters high around and the moat outside of city wall is 52 meters wide.

As the royal residences of the emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties from the 15th to 20th century, the Imperial Palace of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing known as the Forbidden City in Beijing was the center of State power in ancient China. It was constructed between 1406 and 1420 by Ming emperor Zhu Di and witnessed the enthronement of 14 Ming and 10 Qing emperors over the following 505 years. The Forbidden City was inscribed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1987.

Located in the center of Beijing, the Forbidden City is the supreme model in the development of ancient Chinese palaces, providing insight into the social development of late dynastic China. The layout and spatial arrangement inherits and embodies the traditional characteristic of urban planning and palace construction in ancient China, featuring a central axis, symmetrical design and layout of outer court at the front and inner court at the rear and the inclusion of additional landscaped courtyards deriving from the Yuan city layout.

As the example of ancient architectural hierarchy, construction techniques and architectural art, it influenced official buildings of the subsequent Qing dynasty over a span of 300 years. The religious buildings, particularly a series of royal Buddhist chambers within the Palace, absorbing abundant features of ethnic cultures, are a testimony of the integration and exchange in architecture since the 14th century. Meanwhile, more than a million precious royal collections, articles used by the royal family and a large number of archival materials on ancient engineering techniques, including written records, drawings and models, are evidence of the court culture and law and regulations of the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Since 1925 the Forbidden City has been under the charge of the Palace Museum, whose vast holdings of paintings, calligraphy, ceramics, and antiquities of the imperial collections make it one of the most prestigious museums in China and the world.

Towers of the Forbidden City (故宫角楼)

The 4 corner towers of lofty walls were established in 1420, rebuilt in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). As one part of the Forbidden City, they served as the defense facility just as the lofty walls, the gate towers and the moat. They rest on the base with Buddhist-style building surrounded with stone columns.

There goes a tale about the construction of them. Zhudi, Emperor Yongle of the Ming Dynasty, ordered the chief project commander to build four fine corner towers, each with 9 girders, 18 posts and 72 ridges. The chief project commander gathered all the foreman and carpenters together and gave them three months to fulfill the mission. This was really a bitter pill to swallow as nobody had ever seen such a complicated yet delicate corner tower. Deep in worry, a carpenter met an old man selling grasshoppers and bought a grasshopper cage for relief. To his surprise, the delicate grasshopper cage with layer upon layer had just 9 girders, 18 posts and 72 ridges. Thereafter the design was brought out. It is said that the old man was the father of the builders, Luban. This is definitely nothing but a tale.

However, the four of the Forbidden City inherited the flexibility of the traditional wood structure construction and the skillful combination of the function and decoration indicated the superb and excellent craftsmanship of ancient Chinese craftsman.

Hall of Mental Cultivation (养心殿)

The Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin dian) was built in 1537 and rebuilt during the Qing emperor Yongzheng's reign (1723-1735). The "I"-shaped buildings are divided into two parts - the front halls and the rear halls. The chamber was moved to the rear halls after the emperor Yongzheng. The central rooms and the west rooms of the front halls were changed into the place where emperor handled the state routine affairs,reviewed memoranda and received his officials.

The east room was the place where the empress dowagers Cixi and Cian took charge of the state affairs behind a screen when the emperors Tongzhi and Guangxu were in their childhood. The Qing last emperor Puyi (r. 1909-1911) convinced the "presence meeting" and made the decision to give up the throne after the revolution of 1911 broke out.

Palace of Longevity and Health (寿康宫)

Construction of the Palace of Longevity and Health took place from December 1735 (the thirteenth year of the Yongzheng reign) to October 1736 (the first year of the Qianlong reign). It was Qianlong Emperor who ordered this palace built for his mother, Empress Dowager Chongqing. Since then it became the palace exclusively reserved for empress dowagers. After multiple renovations during the reigns of Jiaqing (r. 1796-1820), Daoguang (r. 1821-1850), Xianfeng (r. 1851-1861) and Guangxu (r. 1875-1908), it had a layout basically unchanged. The imperial dowager consorts lived in the Western Palace of Longevity (Shou xi gong), Middle Palace of Longevity (Shou zhong gong), and the First Abode (tousuo) among other living quarters which were nearby the Palace of Longevity and Health. The East Side Hall was a throne room reserved exclusively for the Emperor when he visited the Empress Dowager’s residence.

Palace of Compassion and Tranquility (慈宁宫)

The Palace of Compassion and Tranquility (Cining gong), first built in 1536 in the west of the Forbidden City, was the palatial residence especially built for Empress Dowager Jiang at the order of the Jiajing Emperor (r. 1522-1566). In 1769 (the thirty-fourth year of Qianlong reign, Qing dynasty), the main hall of Palace of Compassion and Tranquility was rebuilt with multiple-eaves, and the rear hall was moved further north, in a layout as seen today. The courtyard, bounded by the east and the west covered corridors, which connect the Gate of Compassion and Tranquility to the south and the wing houses of the rear hall to the north, forms an independent architectural complex. The main hall, with front and rear verandas, a gable and hip roof with double eaves and in yellow glazed tiles, is seven-bay wide and five-bay deep. In front of the main hall is a moon terrace, where the major ceremonies for the empress dowager took place. Especially on the Empress Dowager’s birthdays, it was where the emperor held celebrations. The rear hall was where the Empress Dowager worshiped the Buddha, and was furnished with all sorts of statues of Buddha and ritual instruments, thus it was also named the “great Buddha hall”.

Palace of Gathered Elegance (储秀宫)

The Palace of Gathered Elegance (Chuxiu gong) is located in the northeast of the Six Western Palaces. Notable among the consorts who lived here throughout the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties was the Empress Dowager Cixi. She lived here when she was young as Consort Yi. In the rear hall, she gave birth to Zaichun, the only son of the Xianfeng Emperor (r. 1851-1861) and became the Tongzhi Emperor (r. 1862-1874). Walls of the roofed corridors in the courtyard are inscribed with a Long Life Odes by the courtiers for her fiftieth birthday.

Palace of Earthly Honor (翊坤宫)

Built in 1417, the Palace of Earthly Honor (Yikun gong) was originally named Palace of Myriad Peace (Wan'an gong), and called the present name during the Ming Jiajing reign (1522-1566). It was the residence of emperesses and concubines in the Ming and Qing dynasties.

On grant ceremonies,empress dowager Cixi would receive respects here from imperial concubines.On her fiftieth birthday in 1884,the empress dowager Cixi once received congratulations from courtiers here.

Palace of Eternal Longevity (永寿宫)

In the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the Palace of Eternal Longevity (Yongshou gong

) was the residence of the Empress. The Chongzhen Emperor (1628-1644) once moved here to fast as a penance to Heaven because of frequent natural disasters. In the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), it was a residence for some important imperial concubines. Concubine Ru of the Jiaqing Emperor (1796-1820) lived here for some time during the Qing dynasty.

Palace of Earthly Tranquility (坤宁宫)

North of the Hall of Union (Jiaotai dian), the Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunning gong) was built for the chief consort of the emperor. During Qing times, the Palace was remodeled into a Manchu-style house, which was dubbed "pocket house” (koudai ju): the house has its main door off center to the east rather than in the middle; wooden panel doors replace lattice doors; windows open from the bottom (swinging out on hinges fastened at the top) and are propped up by sticks. Inside the Palace, along the north, the west, and the south walls are linked heated brickkangplatforms. The Palace of Tranquility was at once the Shamanism sacrificial hall and the imperial bridal chamber. It still retains the original décor today.

In Qing times, the empress did not live here. It was the bridal chamber for the Kangxi (r. 1662-1722), Tongzhi (1862-1874), Guangxu (r. 1875-1908), and the abdicated Xuantong (r. 1909-1911) emperors. The couples only spent their first two days of marriage in this palace. Then they moved to live in the Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing gong) or the Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin dian).

Palace of Prolonging Happiness (延禧宫)

The Hall of Prolonging Happiness (Yanxi gong) was destroyed by fire during the Daoguang reign (1821-1850). In 1931, a few years after the Palace Museum was founded, three two-storied warehouses were built for storing artifacts. In 2005, the museum installed the Research Center for Traditional Calligraphy and Paintings in the east warehouse, the Research Center for Ceramics in the west warehouse, and a Ceramics Laboratory in the central warehouse.

It used to be the residence of consorts and concubines during the Ming and the Qing dynasties. After the destruction, it remained in ruin. In 1909, the Qing government initiated the construction of a western-style "Hall of water” in a pool. The hall is built on a white marble base, with iron cast and glass walls and floors. By its completion, water would be filled into the poll surrounding the hall, so that people inside the pavilion could view the swimming fish through the transparent glass walls. It is popularly known as the "crystal palace". However, not long after the project was launched it stopped due to the tight budget. Now, the marble carvings and the iron cast are only for visitors to imagine.

Palace of Eternal Spring (长春宫)

The Palace of Eternal Spring (Changchun gong) is one of the Six Western Palaces, where the emperor's consorts would reside. Upon her regency of the Tongzhi Emperor (r. 1862-1874), the Empress Dowager Cixi made this palace her residence, until her fiftieth birthday when she moved to the Palace of Gathered Elegance (Chuxiu gong).

There is a veranda extended from the rear of the Hall of Manifest Origin (Tiyuan dian), a hall to the south of the Palace of Eternal Spring. The veranda was used as a theatrical stage, where the Empress Dowager Cixi would watch opera performances from here. On the walls of the corridors around the courtyard of the Palace of Eternal Spring are a series of eighteen paintings of scenes fromDream of the Red Chamber. This novel, written by Cao Xueqin, is one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature and is universally considered one of the greatest novels of China.

Palace of Heavenly Purity (乾清宫)

The Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing gong) was built in the early fifteenth century as the emperor's principal residence. Having been rebuilt several times after conflagrations, the current building is datable to 1798, the third year of the Jiaqing reign (1796-1820).

From the Yongle Emperor (r. 1403-1424) of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) to the early Qing dynasty (1644-1911), the Palace of Heavenly Purity was the place where emperors slept and worked. Their coffins were held in this palace before burial for several days of a ritual procedures and demonstrating a man's peaceful death in his own place. Beginning in the Yongzheng reign (1723-1735), the Palace of Heavenly Purity was no longer a residence. The nearby Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin dian) took over that function. However, it still a venue in which emperors conducted routine government business and celebrated major festivals and rituals. "Banquets for a thousand elders” (qiansou yan) were held here in the Kangxi (r. 1662-1722) and Qianlong (r. 1736-1795) reigns.

Hanging high above the throne is a signboard inscribed with "Upright and Pure in Mind” (Zhengda guangming) by the Shunzhi Emperor (r. 1644-1661). The Yongzheng Emperor initiated the custom of placing the name of the heir apparent in a box that was hidden behind this panel. The emperor also carried the designated heir's name. Upon the old emperor's death, the names were compared and, when satisfactorily confirmed, the successor declared.

Palace of Tranquil Longevity (宁寿宫)

The Palace of Tranquil Longevity is located behind the the Hall of Imperial Supremacy (Huangji dian). It was first built in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), and was renovated in the Kangxi reign (1662-1722) as the residence of the Empress Dowager. Now the east and west corridor rooms to the south of it have been converted into galleries of the Treasury Gallery, exhibiting palace paraphernalia and the accessories of emperors and empresses.

Palace of Great Benvolence (景仁宫)

Built in 1420, this Palace was the residence of imperial concubines in the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. In 1654, the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1662-1722) was born in this hall.

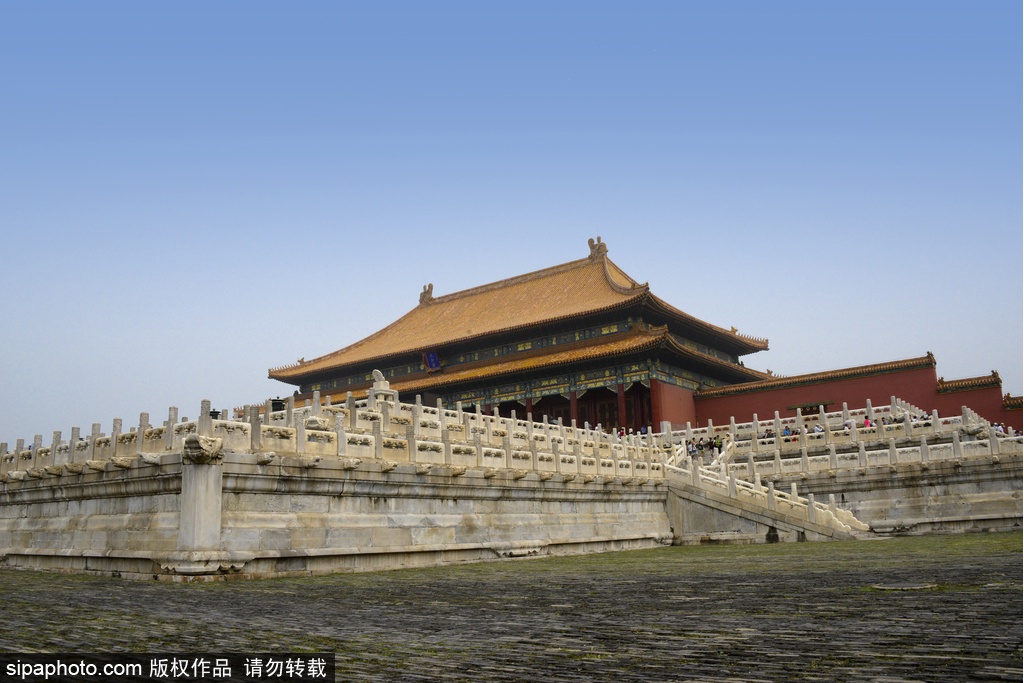

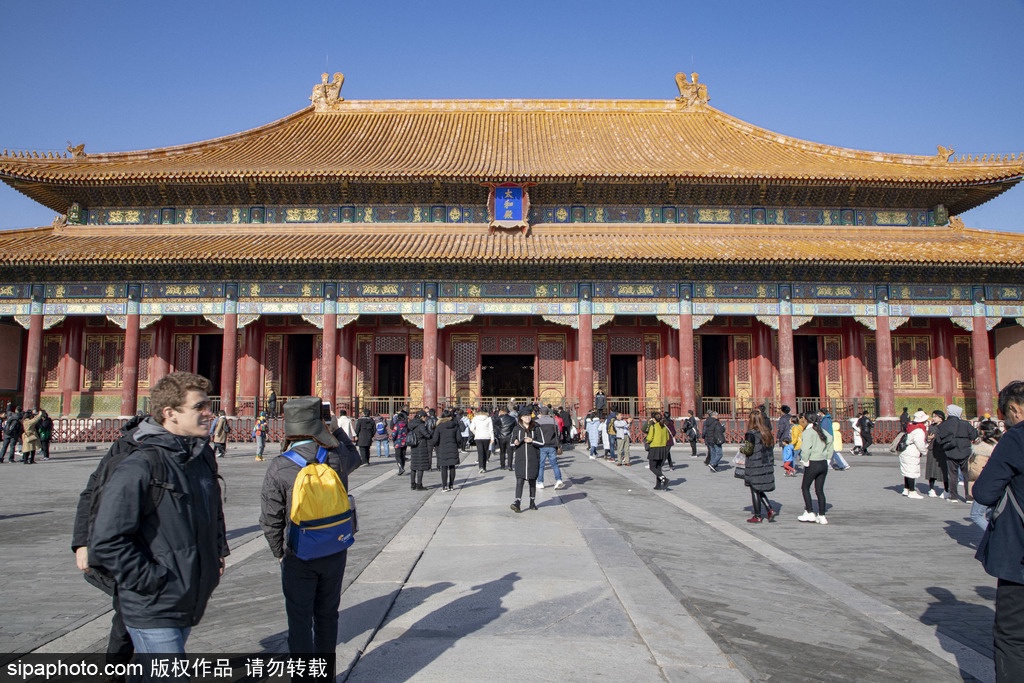

Hall of Supreme Harmony (太和殿)

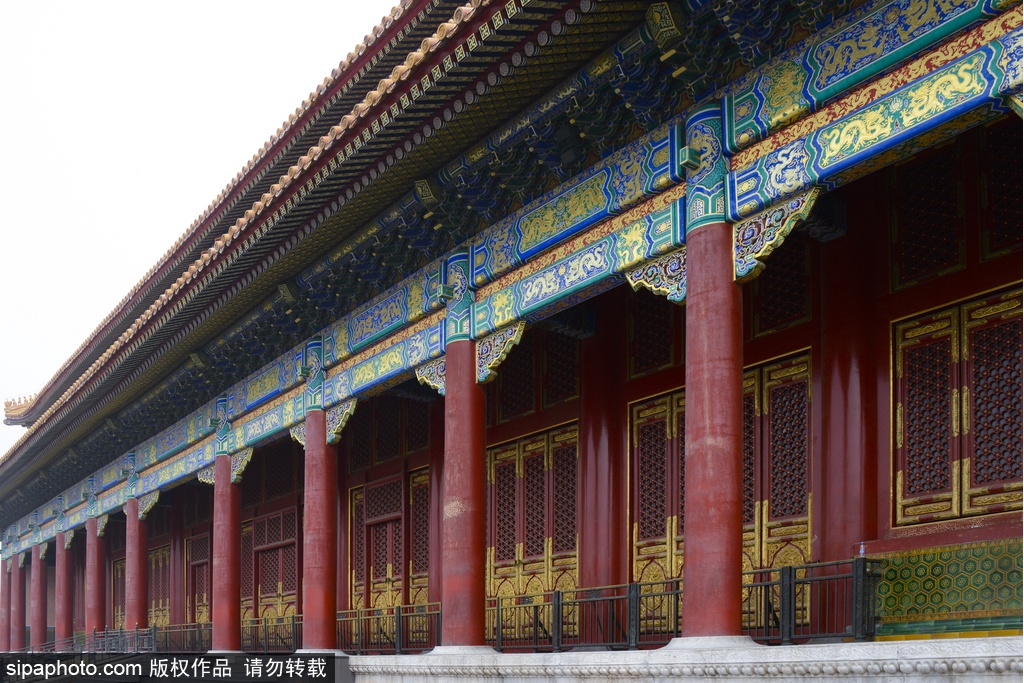

The Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe dian) is the most dignified building in the Forbidden City, and is commonly referred to as the Hall of Golden Chimes (Jinluan dian). Built in the early fifteenth century (the Yongle reign), it was burned to the ground within months of its dedication. The Jiajing Emperor (r. 1522-1566) renamed it the Hall of Imperial Supremacy (Huangji dian), and upon making Beijing their capital, the Qing rulers quickly changed to the present name. Its name reflects the significant sociopolitical ideal of universal harmony under heaven. The current building was reconstructed during the Kangxi era (1662-1722).

The Hall of Supreme Harmony sits in the center of the Forbidden City, on the Imperial Way (yu lu) – the remarkable section of the invisible central axis of the city. As the Imperial Way ascends the white marble three-tiered terrace it is carved with dragon patterns that extend all the way through the throne hall. During grand rituals or ceremonies, the emperor ascended the throne to imperial music, inspecting the empire as far as he could, receiving greetings and congratulations from his subjects.

The Hall of Supreme Harmony is the largest hall in the Forbidden City, and architecturally the highest-ranking building of the surviving traditional architecture in China. Golden dragon designs dominate the hall's exterior and interior décor. The ten figurines at each of its roof corners distinguish it as superior to other ancient buildings.

Hall of the Supreme Principle (太极殿)

Upon its completion in the Ming dyansty (1368-1644), the Hall of Supreme Principle (Taiji dian) was the residence of consorts and concubines. In the late Qing dynasty (1644-1911), it was renovated and united with the Palace of Eternal Spring (Changchun gong) as a large compound. The current name was designated at that time. In the late Qing dynasty, the Empress Dowager Cixiand Longyu resided here.

Hall of Preserving Harmony (保和殿)

The third of the Three Ritual Halls, the Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe dian) was completed in the early fifteenth century. It was first called Hall of Scrupulous Behavior (Jinshen dian), was changed to Establishing Supremacy (Jianji dian), and was finally named Hall of Preserving Harmony - with the implication of preserving the unity of one's inner spirit, and sharing harmony under heaven.

In Ming dynasty (1368-1644) times, before attending a grand ritual or ceremony, the emperor left from his residence in the Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing gong) in the Inner Court and was brought to the Hall of Preserving Harmony to change into ceremonial robes.

In Qing times, the hall served as the wedding venue for the Shunzhi Emperor (r. 1644-1661), and as a temporary residence for him and his successor, the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1662-1722), when the three main halls in the Inner Court were under restoration. Every New Year's Eve and on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month (that is, the full moon), emperors held banquets in the Hall of Preserving Harmony to entertain heads of states, imperial kinsmen, and ministers higher than the second rank. From 1789, every three years the Palace Examination was held here.

Galleries:

The Gallery of Clocks

Open to visitors since January 17, 2019, the new Gallery of Clocks is located in the buildings south of the Hall for Ancestral Worship (Fengxian dian). The gallery features eighty-two timepieces from the Museum’s collection; of these, twenty-one were made in China and sixty-one were manufactured overseas. Twenty of the pieces now on view have never before been displayed to the public. The permanent exhibition has six sections showcasing timepieces from the Qing imperial workshops, Guangzhou, England, France, Switzerland, and other countries. Divided into two exhibition spaces, the gallery especially highlights clocks manufactured or acquired during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911).

From its inception thirty years ago, the Gallery of Clocks has been housed in a few locations within the Forbidden City. After occupying space in the Palace of Eternal Harmony (Yonghe gong), Hall for Ancestral Worship, and the east galleries of the Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe dian), in September of 2004 the gallery was once again installed within the Hall for Ancestral Worship. After over ten years, the gallery’s furnishings and facilities had become outdated and in need of renovation. Meanwhile, the Palace Museum’s curators had been planning to return the historical hall to its period décor.

The new space is expertly designed to highlight the unique artistry of the historical English, French, Swiss, and Chinese clocks. The east and west sides of the gallery display furniture and other objects from the collection to complement the timepieces. Although the new gallery occupies a smaller area than the previous space, the exquisite pieces seen in the original gallery remain on view. For example, the renowned gilded-copper clock with a mechanical figure writing in Chinese and a gilded-copper clock with an elephant pulling a carriage are among the works from the previous displays included in the new gallery. With upgraded displays and facilities, the gallery is able to highlight the beauty of the works on view.

After the gallery’s relocation, the Hall for Ancestral Worship is now undergoing renovation; after the period décor is restored, the space will be open to visitors. Additionally, the Museum is preparing the area of the Palace of Prolonging Happiness (Yanxi gong) as an exhibition space for the many works of foreign art in the collection. Some of the most exquisite Western clocks in the collection will be on view in that planned space.

The Furniture Gallery

The Palace Museum’s Furniture Gallery opened in September of 2018. Dedicated to one specific form of art, the gallery is similar to the Ceramics Gallery, Calligraphy and Painting Gallery, and other galleries showcasing their respective forms of art. The initial exhibition space of the Furniture Gallery is located in the southwest sector of the Forbidden City in an area known as the South Storehouses. This first-phase exhibition includes a display of over 300 pieces or sets of Qing-dynasty (1644–1911) furniture used by the imperial court.

The curatorial plan includes three phases. In the first-phase exhibition space, in addition to the display of over 300 works of Qing furniture, another group of over thirty exquisite pieces or sets of furniture from the Kangxi (r. 1662–1722), Yongzheng (r. 1723–1735), and Qianlong (r. 1736–1795) reigns are presented in scenes of courtyards, scholarly studios, music rooms, or other thematic displays with state-of-the-art multimedia features and lighting. These displays recreate scenes from the Qing dynasty as seen in works such asPainting of Hongli “Is One, Is Two” by an Anonymous Qing Dynasty Artist (Qingren hua Hongli shiyi shier tu).

The Palace Museum currently has over 6,200 pieces or sets of Ming (1368–1644) and Qing furniture in its collection; many of these works are rare and the most superb examples of certain furniture types from those periods. For many decades, these treasures of imperial furnishings have been stored deep within the Museum’s collection storehouses. Beginning in 2015, the administration began to expand the areas accessible to the public and increase the number of items on view. At the time, the South Storehouses were designated as an exhibition space for court furniture. After almost three years of planning and renovation, the South Storehouses were opened in the fall of 2018 as a modern space for storing and showcasing exquisite examples of dynastic furniture.

In his introduction to the Furniture Gallery, the Palace Museum’s Director Shan Jixiang noted that much of the furniture in the Museum’s collection is preserved in above-ground storehouses in tightly-packed spaces. Since many of the palatial halls and courtyards feature period décor with furniture arrangements, the Furniture Gallery with its “warehouse style” presentation, he notes, offers a creative way to share the Museum’s holdings with the public in a manner compatible with conservation principles. Since the furniture has always been stored at room temperature, the exhibition spaces are outfitted with air-circulation systems but will not be air conditioned.

According to the curatorial plan, the Furniture Gallery’s three phases are divided among two areas within the Forbidden City’s southwest sector. The first and second phases will both be opened in the area of the South Storehouses while the third will be located in the area of the Hall of Southern Fragrance (Nanxun dian). With over 2,000 pieces or sets of furniture, the exhibition spaces will serve as both storehouses and galleries. The second phase is designed as a warehouse-style display. The third phase will primarily showcase Ming furniture. In the future, the featured works may change to offer the public a chance to see more of the collection. Eventually, the three complete phases will be complemented with new exhibition spaces in the Hall of Martial Valor (Wuying dian) and the Hall of Embodied Treasures (Baoyun lou).

The Tools of War Gallery

"In times of peace, do not forget to be ready for war".A hall for archery was first built in front of the Hall for Ancestral Worship (Fengxian dian) during the reign of the Shunzhi Emperor (r. 1644-1661) in the early Qing, when mounted archers were brought into the core of the dynasty's military forces. The Kangxi Emperor (r. 1662-1722) later led his sons and those bodyguards who were skilled archers to shoot arrows here. The hall was then transformed into the Archery Pavilion (Jian ting) during the subsequent Yongzheng reign (1723-1735), following which the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1795) summoned the best candidates of the impeiral military examination here and presided over final examinationsfor archers and horsemen. During the later Jiaqing reign (1796-1820), candidates for the final stages of the imperial military examiniation were tested outside the Pavilion of the Purple Light (Ziguang ge), while the Archery Pavilion saw tests of archery, blade, and stone dumbbell.

The Qianlong and Jiaqing Emperors had the slogan "Speak the Manchu language, practice archery and riding" inscribed on a stone tablet erected in the pavilion.

Gallery of Historic Architecture

The Gallery of Historic Architecture in vicinity of East Prosperity Gate occupies four major sections: the city wall between the Meridian Gate (Wu men) and the East Prosperity Gate, the southeast corner watchtower, the East Prosperity Gate, and the area around the office of Imperial Procession Guards (luanyi wei). The city wall section does not house exhibitions but serves as the major passageway between the historical buildings and the key venue for outdoor displays. The corner watchtower is the home to the themed exhibition “Timber Structures of Historic Architecture”, featuring such contents as multi-media productions, architectural drawings and charts (with a three-sided cone rotating display fixture), the main structure and model of the watchtower. The exhibition gallery at the East Prosperity Gate hosts the special exhibition “Ancient Architectural Designs”, consisting of four units: “Planning and Design”, “Interior Decoration and Design”, “Tilework and Design” “Colored Painting and Design”. The exhibition gallery in the Office of the Imperial Procession Guards has the themed display “Masonry and Preservation of Historic Architecture”, including warehouse-style exhibition area for stone relics, conservation studio for stone relics and a service area for the public.

The Gallery of Historic Architecture, for the first time, combines the East Prosperity Gate Tower, the southeast corner watchtower, the city wall, and a ground gallery, providing visitors with an exciting three-dimensional experience. The gate tower exhibition will showcase exquisite architectural components, pressed models by Chinese Architect Family Lei, and design drawings; a pathway to the rooftop is also built to provide a close-up view of the structural components and colored paintings. The city wall between the Meridian Gate and the East Prosperity Gate is also open to the public, offering a fabulous aesthetic experience of the architecture; the southeast corner watchtower is now accessible, so is the beauty of its brilliant structure, which is also brought to view via digital production The Corner Watchtower. The area around the Office of the Imperial Procession Guards will be an open stone sculpture garden to showcase quality stone structures from the museum’s collection. Viewing these sculpted stone relics high above from the gate tower will take the visitors to experience an engaging historical atmosphere.

The Sculpture Gallery

The Palace Museum Sculpture Gallery is located in the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility, with five exhibition galleries entitled: Supreme Sculpture, Han and Tang Terracotta Figures, Stone and Brick Reliefs, Xiude White Stone, and Buddhist Statues. The display area is about 1,375 square meters, with a total of 425 exhibits.

The exhibits on display in the Sculpture Gallery are grouped into three themes: terracotta figures, stone and brick reliefs, and Buddhist statues. The terracotta figures, dating from the Warring States period (475-222BCE) to the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) with masterpieces created through the ages, constitute a complete development history. The displayed items include the world-renowned Terracotta Warrior of Qin Shihuang; most of them were made in the Han (206BCE-220CE) and Tang (618-907) dynasties. The stone reliefs unearthed in northern Shaanxi and Southwestern Shanxi areas are diverse in content and form. The white stone Buddhist statues of Quyang, Hebei Province, employed perforating techniques and diversified the craftsmanship. These statues, dated from the Northern Wei dynasty (386-534) to the Sui (581-618) and Tang dynasties, are organized in chronological order. The Palace Museum was established on the basis of the Ming and Qing imperial palace, where the court collections held the Tibetan Buddhist copper statues dated to Yongle (r. 1403-1424) and Xunde (r. 1426-1435) periods. These statues in their rounded regularity are solemnly graceful, which marks the characteristic of Ming court style. The statue of the sixth Panchen Lama is a classic of Tibetan Buddhist statues created in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

Although the pre-modern Chinese artisans created numerous masterpieces of sculpture, these precious statues were long regarded as “contrivances” and being overlooked due to the conditioning of traditional ideology. Since its establishment, the Palace Museum has aimed to strengthen the collection of sculpture art. Especially after the founding of People's Republic of China, by accepting public donations, archaeological excavations, exchanges and collaboration with other domestic museums, among others, the museum’s collection is greatly enriched; combined with the original regal collections of Ming and Qing dynasties, the systematic collection of sculptural relics is nearly complete. In 1958, the Palace Museum established the Sculpture Gallery in the Hall for Ancestral Worship (Fengxian dian); it is the first themed gallery of sculpture in the history of Chinese museums, and widely acclaimed from all walks of life. This year marks the ninetieth anniversary of the founding of the Palace Museum. Leveraging the inherited tradition and recent research achievement, the newly renovated Sculpture Gallery aims to provide the visitors a more comprehensive and objective understanding of the historical development of Chinese ancient sculpture.

The Treasure Gallery

The Treasure Gallery is a series of exhibition spaces in the northeast part of the Forbidden City in an area of the Museum known as the Palace of Tranquil Longevity Sector (Ningshou gong qu). It consists of six gallery rooms displaying pieces from the imperial collection and extant accoutrements for palace life. All of these exquisite items are made of precious materials, such as jade, jadeite, gold, silver, pearls, and other precious and semi-precious stones. The superb craftsmanship and inestimable value of each piece is aptly summarized in the title of the gallery.

Occupying a large area in the northeast of the Forbidden City, the Palace of Tranquil Longevity Sector was originally designed as the private paradise of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1795) for after his retirement from imperial duties. The courts in this sector contain expansive halls, intimate residential chambers, a grand theatre (now the Gallery of Qing Imperial Opera), a scenic garden, and solemn Buddhist shrines. The overall layout of this rectangular sector is modeled after the Forbidden City. This relatively secluded and independent area creates the perfect environment for displaying the treasures of dynastic glory.

The Bronze Gallery

The Bronze Gallery is located to the east of the Forbidden City’s three rear halls within the Palace of Celestial Favour (Chengqian gong) and the Palace of Eternal Peace (Yonghe gong). These magnificent structures are located among a cluster of small courtyards that served as the living quarters of the imperial family during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). The two palaces have been fitted with new installations and are now known collectively as the Bronze Gallery. Situated on opposite sides of a paved corridor, the two halls were both built in the early-Ming period (Ming dynasty, 1368–1644). Even after hundreds of years, the architecture has been preserved in the original Ming style in spite of repairs made during the subsequent Qing dynasty.

The historic halls are a suitable location for the Palace Museum’s bronzes. With more than 15,000 bronzes in the collection, the Museum has one of the largest holdings of bronze artifacts in China. Two-thirds of these pieces date to the pre-Qin period (before 221 BCE). Currently on show is a fine selection of ritual bronze vessels from the Shang and Zhou dynasties (ca. 16th–3rd c. BCE). These ancient works display the technological sophistication of early metal casting. The early forms of Chinese characters cast into the vessels demonstrate the important governmental functions the vessels served in ancient Chinese society. The gallery also exhibits many ink rubbings of the inscriptions on the vessels.

The development of bronze and the cultural significance with which it is associated represents an important step in the development of human civilization. In China, large bronze artifacts dating to the late-Xia dynasty (also known to archaeologists as the Erlitou period; Xia dynasty, ca. 21st–17th c. BCE) have been unearthed in China. Archaeologists have discovered quantities of bronzes with diverse and complex designs from the early-Shang (or Erligang period; Shang dynasty, ca. 16th–11th c. BCE) and the late-Shang dynasty (or Yinxu-culture period). Articles cast after the Zhou dynasty (ca. 11th–3rd c. BCE) feature lengthy inscriptions that record important events. The designs and inscriptions on these ancient vessels are part of what makes China’s bronzes unique. The significance of the production and development of bronze on pre-Qin Chinese society cannot be underestimated.

According to legendary accounts, Yu the Great cast the Nine Cauldrons (ding) during the Xia dynasty as a symbol of his divine mandate to rule. The cauldrons continued as physical representations of authority throughout the Shang and Zhou dynasties and were moved to various centers of power as one ruler was deposed and another rose in dominance. During the Spring and Autumn Period (770–ca. 475 BCE), the Zhou dynasty’s power was diminished, and the Chu rose as a powerful rival. Some of the kings of Chu challenged the authority of the Zhou by inquiring about the cauldrons—an act of defiance and subversion. Various ding-tripods, ding-tetrapods, and other bronze vessels for ceremonial use have been unearthed among the ruins of ancestral shrines and burial chambers; those vessels designed for such ceremonial use are known as ritual vessels (liqi) and were prescriptively designed and used according to the status of the pre-Qin noble classes. This hierarchical system of design and use was part of the development of ritual theory and practice up through the Western Zhou period (ca. 1046–771 BCE) and culminated in the eventual codification of the system inRites of Zhou (Zhou li). The story of these nine cauldrons specifically and bronze artifacts in general are now important symbols of China’s national, historic, and cultural cohesion.

Since the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the Chinese have been unearthing artifacts from earlier periods. Many emperors throughout China’s dynastic history have been captivated by the impressive design of bronze vessels. Seen as auspicious objects, officials would offer bronzes to the imperial court, and emperors issued orders for their subjects to find the ancient artifacts. During the Song dynasty (960–1279), the imperial court compiled the illustrated Xuanhe Catalogue of Antiquities

(Xuanhe bogu tulu). The Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736–1795) of the Qing dynasty arranged the compilation of illustrated catalogues such as Western Qing Appraisal of Antiquities(Xiqing gujian),Western Qing Supplemental Appraisal: First Edition(Xiqing xujian jiabian),Western Qing Supplemental Appraisal: Second Edition(Xiqing xujian yibian), andAntiquity Appraisal of Tranquil Longevity(Ningshou jiangu). Almost 1,600 of the Museum’s more than 15,000 bronzes are inscribed vessels dated to the pre-Qin period. The Bronze Gallery is designed to highlight the intersection of China’s historic bronzes and the culture of the imperial clan.

Gallery of Painting and Calligraphy

The Hall of Literary Brilliance (Wenhua dian) is the main building in an architectural compound that lies to the far east of the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe dian).

It was the residence of the heir apparent during the early period of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), with green glazed tiles covering the roof. Since 1536, it was reserved for the emperor as his secondary hall. Accordingly, the tiles were changed into yellow, the color of the emperor. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the imperial lecture was regularly held in this hall and papers of the "Palace Examination” were reviewed here, too. Those prominent mandarins would feel so honored to be given the title of the "Grant Secretary of the Hall of Literary Brilliance”.

Recommended routes:

One-day Tour:

1. The Meridian Gate(Wu men)

2. "Painting and Calligraphy Gallery"

Hall of Martial Valor (Wuying dian)

3. "Ceramics Gallery"

Hall of Literary Brilliance (Wenhua dian)

4. Gate of Supreme Harmony (Taihe men)

5. Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe dian)

6. Hall of Central Harmony (Zhonghe dian)

7. Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe dian)

8. Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing gong)

9. Hall of Union (Jiaotai dian)

10. Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunning gong)

11. Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin dian)

12. Area of Six Western Palaces

13. Imperial Garden (Yu huayuan)

14. Area of Six Eastern Palaces

15. "Hall of Clocks"

Hall for Ancestral Worship (Fengxian dian)

16. "The Treasure Gallery, Gallery of Qing Imperial Opera"

Area of Palace of Tranquil Longevity (Ningshou gong)

Half-a-day Tour (Plan A):

1. The Meridian Gate (Wu men)

2. "Painting and Calligraphy Gallery"

Hall of Martial Valor (Wuying dian) or "The Ceramics Gallery"

Hall of Literary Brilliance (Wenhua dian)

3. Gate of Supreme Harmony (Taihe men)

4. Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe dian)

5. Hall of Central Harmony (Zhonghe dian)

6. Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe dian)

7. "Hall of Clocks"

Hall for Ancestral Worship (Fengxian dian) or "Treasure Gallery, Gallery of Qing Imperial Opera" The Palace of Tranquil Longevity Sector (Ningshougong qu)

8. Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing gong)

9. Hall of Union (Jiaotai dian)

10. Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunning gong)

11. Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin dian)

12. Area of Six Western Palaces or Area of Six Eastern Palaces

13. Imperial Garden (Yu huayuan)

14. Gate of Divine Prowess (Shenwu men)

Half-a-day Tour (Plan B)

1. Meridian Gate (Wu men)

2. Hall of Martial Valor (Wuying dian): Painting and Calligraphy Gallery

3. Gate of Supreme Harmony (Taihe men)

4. Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe dian)

5. Hall of Central Harmony (Zhonghe dian)

6. Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe dian)

7. Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing gong)

8. Hall of Union (Jiaotai dian)

9. Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunning gong)

10. Area of Six Eastern Palaces (Dong liugong qu)

11. Hall for Abstinence (Zhai gong)

12. Outer Court of Palace of the Tranquil Longevity Sector (Ningshougong qu): Treasure Gallery and Stone Drum Gallery

13. Inner Court of Palace of the Tranquil Longevity Sector (Ningshougong qu): Treasure Gallery, Opera Gallery, and the Well of Consort Zhen (Zhenfei jing)

Applications

The Palace Museum Exhibitions

故宫展览

An online anthology of the Palace Museum's past and current exhibitions (since 2005), this Application encompasses rich media presentation of those exhibitions and enables users to review them anytime and anywhere when connected to the Internet.

The Qing Emperor's Wardrobe

清代皇帝服饰

The Palace Museum houses over 180,000 pieces in the textile collection. These exquisite holdings include a wide variety of garments, accessories, uncut fabric, and silk cloth manufactured for imperial use on occasions such as grand ceremonies, ritual sacrifices, and inspection tours. The extensive collection provides ample resources for specific topics in the study of textiles and design as researchers explore various aspects of the source materials, manufacturing process, craftsmanship, symbolism, and structural patterns of the emperor’s attire. Moreover, our researchers have exhaustively referenced the historic work Illustrated Precedents for the Ritual Paraphernalia of the Imperial Court. This meticulously detailed and painstakingly accurate imperial polychrome edition compiled during the Qianlong reign (1736-1795) provides a comprehensive and systematic manual for the manufacturing, use, and identification of the pieces in the imperial wardrobe.

The comprehensive work corroborates with the Imperial Household Department’s Wardrobe Archive, which preserves daily records of specific garments worn by the reigning emperor. Combined, these two works serve as a reliable first-hand visual and textual resource for the understanding of the regulation of imperial attire in the Qing dynasty. Additionally, comparisons of the depictions of the garments and accessories in the historic illustrated work with vivid imperially commissioned paintings—both of which were created by imperial court painters—shed light on the manufacturing process, occasion, and mode of dress.

The Qing Emperor’s Wardrobe exhibits six types of distinctive imperial garments, namely, court dress, festive dress, regular dress, travel attire, military attire, and casual wear. Each of these types is presented with their respective features and functions. By providing users with a visually appealing and thorough interactive catalogue, the App illustrates the rules and regulations that guided the use of court apparel in the Qing dynasty. Vivid depictions and high-resolution images show intricate detail. Illustrated explanations of the manufacturing process, three-dimensional models of selected garments, and carefully optimized interactive experiences facilitate exciting visual experiences and unique perspectives. Apart from representing the exquisite craftsmanship and stunningly beautiful embellishments, the App also satisfies some widely shared curiosities surrounding the imperial wardrobe and answers commonly asked questions, such as: Who were the imperially commissioned manufacturers? How were these garments made? How much did one set of clothing cost? Which garments were chosen for various occasions?

The Ceramics Gallery in the Pocket

故宫陶瓷馆

The iPhone application Ceramics Gallery in the Pocket(Chinese name: Gugong taoci guan) features all the exhibits in the Palace Museum's Ceramics Gallery located in the Hall of Literary Brilliance (Wenhua dian). All the pieces are chronologically organized by a timeline, which clearly presents users with period characteristics of Chinese ceramics, from the plain earthern pots of the remote antiquity to the sumptuously glazed vases of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). As the name of this application indicates, it is a mobile ceramics gallery you can put in your pocket. While in the physical gallery, the application is your guide at hand, for it provides detailed description of every exhibits displayed there.

365 Days of Masterpieces

每日故宫

Start your day by checking out what we have prepared for you in our newly released smartphone applicationDaily Picks of the Palace Museum (Chinese name:Meiri gugong).

Every day, different works of art. It may be a landscape painting, a sacred Buddhist sculpture, or an exquisitely crafted jade carving, sometimes it can be an interior view of one of the magnificent heritage architecture of the Forbidden City. DownloadingDaily Picks of the Palace Museum, hold the essential Palace Museum in the palm of your hand. The App is developed both for iPhone and Android phone users.

Emperor for a Day

皇帝的一天

Emperorfor a Day is specially crafted by the Palace Museum for children aged between nine to eleven. Follow the guidance of the lion cub for a role-play experience in the great Qing palace to find out what an emperor would do in a single day from dawn till dusk.

Cultural Products and Services

Cultural Products and Services is an independent legal, commercial entity subordinate to the Palace Museum. It is dedicated to the development and sale of cultural products and the promotion of the cultural industry of the Palace Museum. The primary functions of this entity are as follows: develop and sell cultural products in the Palace Museum in accordance with museum regulations; develop multifaceted cooperatives for internal and external representation of the Palace Museum; and produce and sell exhibition-specific products in accordance with museum regulations.